Coughs and Sneezes Spread Diseases: The Spanish Flu in Grey County - Online Exhibit

Coughs and Sneezes Spread Diseases explores the mysterious origins of the Spanish Flu, detailing the path of the virus from its unintended arrival in Canada, the initial confusion surrounding its severity, and its painful human cost. Coughs and Sneezes Spread Diseases also draws comparisons between the responses to a global pandemic in 1918 and 2020.

“Understanding influenza pandemics in general requires understanding the 1918 pandemic in all its historical, epidemiologic, and biologic aspects.”

A Devastating New Enemy

As 1918 began, Canadians continued to support the country’s war effort. After four years of fighting, they believed they knew their enemy well. Little did they suspect that a new foe would surface that spring, and after a brief lull, return with a vengeance that fall. Between 1918 and 1920, this fiendish new villain killed nearly as many Canadians as the war did, an estimated 55,000 in total.

The origins of the Spanish Flu are shrouded in mystery. While theories exist about its origins, scientific study has confirmed that it is a strain of the H1N1 Influenza A Virus. Another strain of this virus caused the “Swine Flu” pandemic of 2009. The 1918 variety earned its nickname from the First World War. Most European and North American countries blocked reports of the disease, fearing that news of widespread illness would lower the morale of soldiers serving overseas and weaken the war effort. News of the pandemic first surfaced in neutral Spain, where reports highlighted the deadly impact of the disease. By the end of the pandemic, approximately one-third of humanity suffered infection, killing an estimated 17 to 50 million people across the globe.

Arrival in Canada

The first wave of the Spanish Flu reached Canada in the spring of 1918, as wounded soldiers carried it home with them in the wake of the First World War. This initial spread acted as most flu infections did, leaving patients with generally mild symptoms. Only those with weakened immune systems suffered significant effects. Once the flu season had passed, Canadians put the virus out of their minds.

Reality Hits

As spring turned to summer, memories of flu season faded away. Somewhere in Europe, the Spanish Flu virus mutated into a more lethal form, able to kill in less than 24 hours. In late August 1918, asymptomatic soldiers, wounded or reassigned, shipped out from Europe. They brought this newer and deadlier version of the flu with them to every corner of the world. By early October, the Spanish Flu arrived in Grey County. Newspaper reports still focused on the war, giving only minor attention to the rising pandemic.

Few understood the medical threat presented by the disease. The October 10, 1918 issue of the Owen Sound Advertiser ran an article under the title “Spanish “Flu” Is Not Serious.” The reporter noted that while there were around thirty cases in town and one should get to bed right away if they notice symptoms, the disease “so far appears to be of a mild type.”

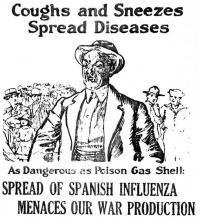

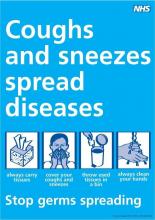

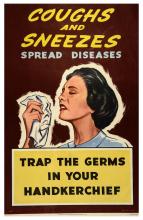

The American government developed the slogan “Coughs and Sneezes Spread Diseases” during the Spanish Flu pandemic to warn the public about how easily it spread. Since 1918, governments around the globe have applied its simple message for respiratory outbreaks, including the COVID-19 pandemic.

Combatting the Flu was a considerable challenge in 1918. There were many obstacles that made it impossible to lessen the pandemic’s deadly impact. Powerful microscopes that could see viruses were not invented until the 1930s. Many skilled medical personnel were serving overseas treating war wounds and could not study the illness. War time censorship made scientific collaboration nearly impossible. Every town and township had its own Board of Health. Each Board of Health made medical decisions independently of other local Boards. Lack of a unified response was one of the greatest weaknesses that enabled the Flu to spread so quickly and widely.

What to Do?

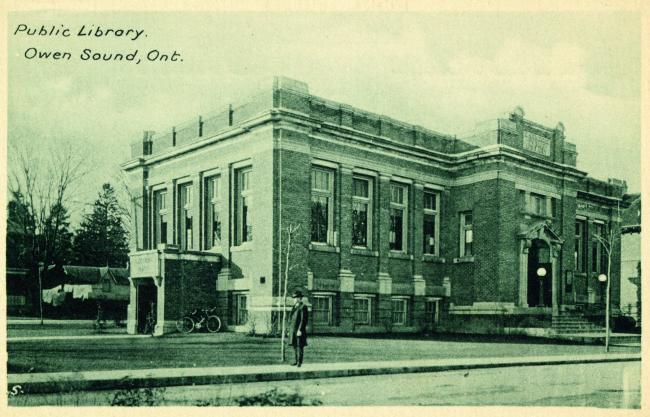

The death count continued to climb, forcing community response. In the Tara area, which was especially hard-hit by the pandemic, the old British hotel was transformed into an emergency hospital. The books in the Owen Sound library were ordered to be fumigated followed soon after by those in the Markdale library.

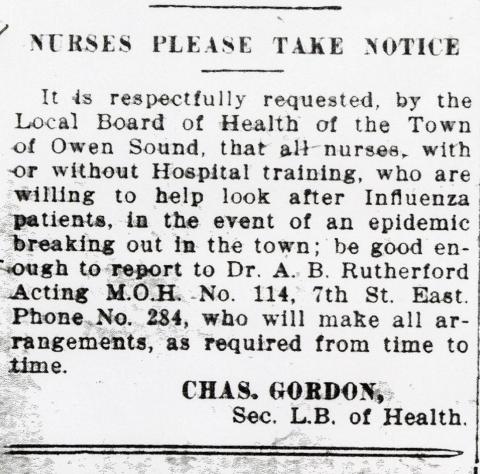

Masks were suggested, and in some places required, as means of slowing the spread. Newspapers included instructions on how to make a simple homemade version from cheesecloth. The local Board of Health requested that anyone with nursing experience or training willing to help treat Flu patients contact the County's Medical Officer of Health..

The Human Cost

The Spanish Flu killed more people than any other pandemic in recorded history. In Grey County, more than 100 people died in the month of October 1918 alone. The strain on medical resources, already stretched thin due to the war effort, made for months of chronic sleeplessness for doctors and nurses. Dr. F. A. Brewster, an Owen Sound doctor who practiced during the pandemic, recalled that medical practitioners regularly consumed nine or ten cups of coffee a day, and slept only two or three hours a night for weeks. Taking a horse and cutter (sleigh) out to check on one patient inevitably meant that others would flag a doctor for help while he was en route. Patients willingly paid the one dollar cost of a doctor’s house call, desperate for help.

While anyone could become ill with the Spanish flu and even die, those aged 25-45 suffered sickness and death more than anyone else. Because these patients were responsible for children, elderly parents, businesses and households, their rapid declines and death in a matter of days or even hours, destroyed generations of families and entire communities.

The Wells Family

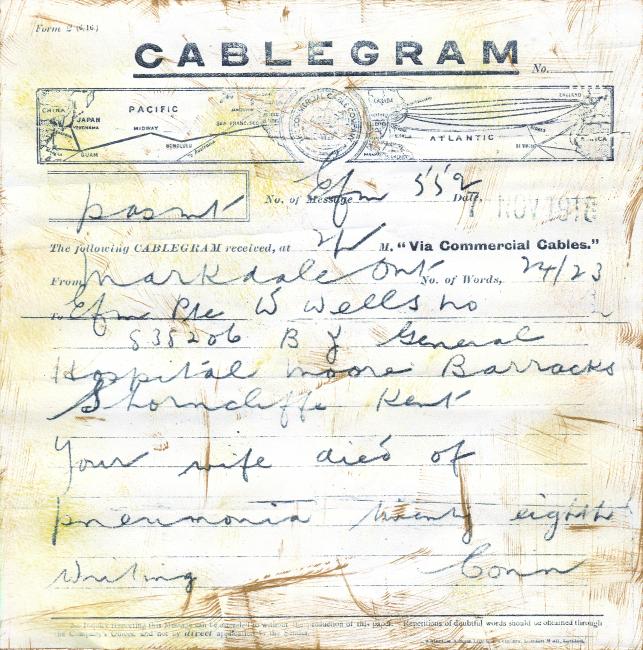

Clara Mae Wells fit the profile of Spanish Flu victims, and the resulting devastation of families. Clara and her husband William, a retired British soldier, arrived in Canada in 1907 with their eldest son and daughter and took up residence in Markdale.

At the first call of war, William re-enlisted with his old British unit and went overseas. By early October 1918, Clara had seven young children to care for and a husband still overseas on active service. Before the end of the month, Clara caught the dreaded Flu and died on October 28, 1918.

No. of Message 552 Date 7 NOV 1918

The following CABLEGRAM received at [?] M. "Via Commercial Cables."

From Markdale Ont. No. of Words, 24/23

To: [?] Pte W Wells no 838206 B J General Hospital Moore Barracks Shorncliffe Kent

Your wife died of pneumonia twenty-eighth

Writing Conn

The family was torn apart at Clara’s passing. With their mother dead and their father still in Europe, the children were separated to be cared for by different local agencies and families. Although reunited briefly upon William’s discharge, eventually the youngest three daughters were adopted by local families, as the strain of single parenthood and the toll of the war overtook the devastated family.

The Evolution of a Virus

More than 90% of Spanish Flu deaths struck in the fall of 1918, but the disease had not yet finished its remorseless march through Canadian homes. Although incidents of infection dropped off by Christmas, the disease returned again with decreasing force in spring 1919 and in the spring of 1920. A combination of genetic mutation and population immunity caused the Spanish Flu virus to lose much of its lethal impact.

The Spanish Flu is an Influenza Type A virus. Influenza A viruses continue to change, adapt and cross species, meaning they are always dangerous and potentially devastating. All of the influenza pandemics of the 20th century and present-day have resulted from Influenza A mutations.

COVID-19 is a disease caused by a novel coronavirus, which means it is a new strain of a coronavirus not previously identified in humans. The Spanish Flu virus contains different genetic material than coronaviruses and is genetically very different. Despite the century between these outbreaks, the preventative and treatment measures are largely the same: physical distancing, isolating the sick, wearing masks and frequent washing for prevention as well as supportive treatment for those infected. Then as now, there was no cure except time, rest, and fate.

Thanks to improvements in medical science, communications, and organization, Canada has better weathered the COVID-19 pandemic than it did the Spanish Flu. In 1919, as a direct result of the high infection and mortality rate, the Canadian government created a new department for public health. The Owen Sound Sun Times lauded the initiative, noting that “(t)he decision of the Federal Government to establish a National Bureau of Public Health…will be hailed…with keen satisfaction all over the country. The helplessness of the Federal authority during the present epidemic is in itself sufficient argument for the reform.” Had this country been hampered as it was in 1918 with comparable death rates, more than 210,000 Canadians would have fallen to COVID-19.

“We have been successful to date, in Grey and Bruce, to limiting the spread and reducing the negative impact that this virus can cause…It is the result of significant collaboration between all sectors and the public.”

In November 2020, Dr. Arra sat down at Grey Roots to discuss pandemics in Grey County, drawing parallels between the Spanish Flu and COVID-19. Click here to watch this fascinating interview.

Artefacts on Display

Click on the boxes below to view the artefacts on display as part of Coughs and Sneezes Spread Diseases.

Physician's Head Mirror, Early 1900s

At the time of the 1918 influenza outbreak, head mirrors were in common use and could be found in many doctors’ bags. They were especially valuable for examining patients’ ears, nose, and throats, acting as a light source during such procedures.

Oil of Eucalyptus Bottle

This tiny medicine bottle contains oil of eucalyptus and was dispensed by the Parker & Co. drugstore, which began in Owen Sound in the 1850s (also see the blue medicine bottle above). For many years, oil of eucalyptus was used to treat respiratory problems, such as asthma, bronchitis, pneumonia and even tuberculosis.

Vaporizer, 1905-1910

Patented in 1897 and again in 1905, this steam croup kettle and other steam-producing equipment could be used at home to open up the lungs, making it easier for pneumonia sufferers to breathe.

Dr. Pollock's Doctor Bag, 1931-1978

As physicians routinely made house calls at this time, doctors needed to carry basic medical equipment and supplies with them. During the pandemic’s second wave in October 1918, there are recorded instances of doctors visiting up to 100 patients in a day.

Invalid Cup, 1891-1930

Used to help a bed-ridden person to take liquid nourishment or medicine, the spout would be tipped into the convalescent's mouth.

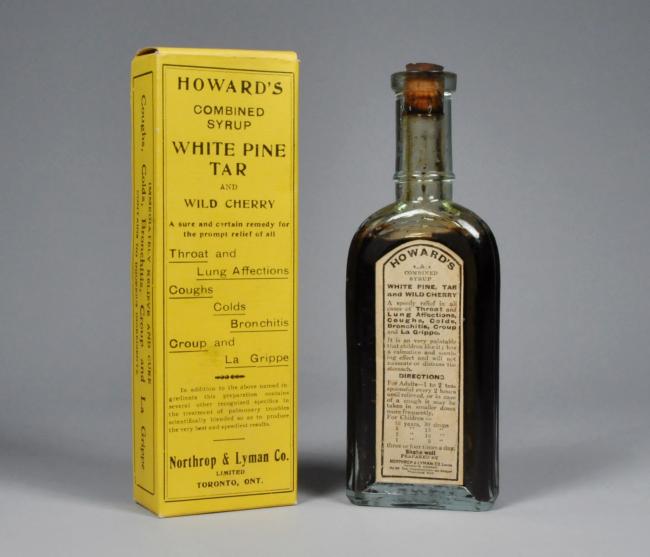

Howard's Combined Syrup Patent Medicine Bottle

Promising “speedy relief in all cases of Throat and Lung Affections, Coughs, Colds, Bronchitis, Croup and La Grippe,” this remedy had no power against the ravages of the Spanish Flu.

Blue Medicine Bottle, 1890-1903

This blue-coloured Parker & Co. bottle likely dates to the 1890s or early 20th-century, when aqua glass was popular. The Parker & Co. drugstore business began under the name of Parker & Cattle. It had a long history and its store locations changed over the years.

Violet Medicine Bottle, 1880-1920

This violet-coloured bottle was made for Dr. Edmund Oldham who practiced in Chatsworth, Grey County. Working around the clock during the pandemic, medical practitioners became worn-down and one of his sons, Dr. Morrell Oldham, a doctor practicing in Desboro and Tara, died as a result of the outbreak.

Robert's White Liniment Bottle

Robert’s White Liniment was advertised as “Fit for Man or Beast.” The claim was that it was a cure-all for everything from sore throats to “lung fever,” chest colds, influenza and congestion. A quack “medicine,” it likely had no effect on influenza virus sufferers.

Muff, 1910-1915

Overcoat, 1910-1915

Rachel McMillen of Proton Township made this matching overcoat and muff for her youngest daughter, Martha Ruth. When the girl was 11, she fell victim to the Spanish Flu, dying on October 24, 1918.

Owen Sound General & Marine Hospital Nursing Graduate's Pin, 1918

The alarming infection Spanish Flu infection rates pulled experienced nurses, recent graduates and even nursing students into action to assist during the pandemic.