The Luxurious Past of Balmy Beach – The King’s Royal Hotel

Accommodation for the travelling public has always been the basic premise of a hotel. One local hotel, however, the King’s Royal Hotel, was much more than simply a place to spend the night. Located in the former McLauchlan Park at Balmy Beach, five kilometres north of Owen Sound, the luxurious and prestigious King’s Royal Hotel quartered many high-class travellers from all over North America and beyond, and won the esteem of many as the “Muskoka of Georgian Bay.” Nonetheless, the hotel’s history was short-lived and enigmatic. Why was this grand hotel knocked down a mere fourteen years after it had been built?

On July 1, 1899, having ownes the land for just one year, ambitious 28 year old John Henry “Jack” McLauchlan (1871-1954) opened “McLauchlan Park” at Balmy Beach. The park included cottages, a pavilion and band stand, a theatre with 25 cents admission, sporting fields and a 400 foot long dock. According to Gayle McLauchlan, there were three fish ponds created: one for bass, one for speckled trout, and one for live alligators. Dr. Lang of Bothwell’s Corners donated young deer and a moose for the park. Others gave caribou and live seals. Thousands of visitors came via ferry, bicycle, automobile, horse, and even foot. In 1900 alone, the ferries brought 52,000 people to the park.[1] The only component missing from the park was accommodation for staying longer than an afternoon. A hotel was needed.

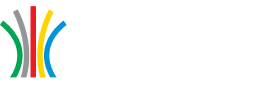

In 1901, after having little trouble selling shares, the Georgian Bay Park and Summer Resort Co. proposed that a large summer hotel be built on the beach. In February 1902, local contractor Alexander Green was given the contract to build the 110 room, $100,000 Spanish-style hotel. Dubbed “Canada’s Most Modern Summer Resort,” the main section of the King’s Royal Hotel was 300 feet in length and three to four stories high. It had a 108-foot tower and observation deck with 1,500 one hundred watt incandescent lights, being one of the first hotels in Ontario to utilize electricity for their lighting system and their electric bell service in each room. Apparently the lights on the tower could be seen from Griffith Island. The King’s Royal was a first-class city hotel with 112 trained, professional staff. It boasted having no bar and noted its policy of strict sobriety. It had long distance telephone capabilities, a spacious rotunda and private balconies, a large main dining room which sat 250 guests, public and private baths, women’s and men’s lounging and smoking rooms, a billiard and ping-pong room, and a barber shop and café. The hotel furnishings cost about $20,000 total.[2] Horse stables, walking and driving trails, the first golf course in the area, tennis courts, boathouses, bowling and croquet greens and even a small museum were added to the already existing theatre and athletic fields on hotel and park grounds. For ten cents, guests could ride a ferry to town and back. The price to stay in this palace? $2.50 per night or $14.00 per week.

No one at the opening of this hotel on July 1, 1902 would have thought that the grand establishment would not exist fourteen years later. Despite early enthusiasm and popularity with the King’s Royal Park and Hotel, by 1904 the hotel was in financial trouble and was sold at auction.[3] There were brief periods of heightened business under new management, with new staff and rates, but nothing lasted. On many days only one or two guests registered. Occupancy was rarely over ten percent of the available rooms. In 1916, the hotel was sold to the Dominion Salvage and Wrecking Co. Ltd. of Toronto for $5,200. Everything inside, including the beautiful oak furniture, the luxurious china and draperies, and even the 1,000 yards of carpet, was auctioned off. The staff had been dismissed, the elegance had been dispersed, and the young and pristine hotel was knocked to the ground. Many of the cottages on Balmy Beach were built from the materials of the destroyed hotel.[4] In this way, at least, the hotel would continue to live on.

But why did the King’s Royal Hotel fail? Many people have attempted to answer this question over the past century. There are many possible answers: the failure of the hotel to accommodate winter guests; the failure of railway companies and newspapers to effectively advertise travel to Balmy Beach; and the inconsistency of the ferry and steamboat service which brought guests from Owen Sound. People blamed the failure of the hotel on the seemingly consistent late rainy springs and, when electrical wires were found cut during numerous events, even on sabotage![5] Others blamed finances. Initial and operating costs were too high and lack of business forced the hotel to offer discounted rates to attract customers, such as $3 Saturday to Monday packages.[6] With these rates, growth and profit was impossible. Others still blamed the war. There was little time to relax and few were able to afford such a vacation while the nation was at war. The ferry and steamboat services had to be completely cut, and many of the men who ran and guarded the already diminishing hotel were sent overseas. Insurance companies refused to insure large Canadian hotels during the war for fear that German agents would burn them down to stop them from being used for the Allied war effort.[7]

All of these factors certainly had a part to play. But perhaps the failure of the hotel had less to do with the botched functions and finances of the hotel itself and more to do with the elitist culture surrounding the elegant estate. Owen Sounders were undoubtedly curious to visit the magnificent establishment, but it’s luxurious and ritzy novelty soon wore thin. It was certainly not the case that Owen Sounders were unsuccessful, lacked sophistication, culture, deportment, and wealth, or that they denied architectural beauty and fashion. But it would be misleading to say that in the early twentieth century the Owen Sound area was not predominantly industrial, agricultural, and traditional. There were, after all, numerous complaints about cows wandering free in the King’s Royal Park. Which makes sense, considering the majority of families at the time owned at least one. The Lord’s Day Alliance and many local churches brought to court and fined the captain of the King’s Royal ferry for operating the vessel on Sundays.[8] Many local, ‘average’ citizens claimed that they lost interest in the hotel because management seemed to only cater to non-locals and the elite. After a short time, the high-class of society decided that Owen Sound and Balmy Beach were no longer fashionable enough for them. They wanted to be seen, and at the time, being seen meant being in Muskoka![9]

In 1916, Balmy Beach said goodbye to the glorious and lavish King’s Royal Hotel. Perhaps it was built before its time – in a time where, in Georgian Bay, tourism was not seen as an effective economic enterprise as it is today. While the King’s Royal may have ultimately failed, J.H. McLauchlan’s vision and enthusiasm foreshadowed the important role that recreation and tourism would play in the future of Owen Sound.

Pictured Top: King's Royal Hotel Postcard (PF49S18F15I4); Bottom Left: Balmy Beach Dock, near King's Royal Hotel, c. 1915 (969.86.17); Bottom Centre: Steamship CANADA near 10th Street Bridge Owen Sound which brought visitors to the King's Royal (PF123S8F8I22); Right: Auction Sale Announcement in the Owen Sound Sun, Tuesday, May 16, 1916 (MF28S1F1I13)

[1] Gale McLauchlan, Balmy Beach… 100 Years (July 1, 1898-July 1, 1998) (Owen Sound: River Edge Self-Publishing, 1998), 10.

[2] Andrew Armitage, “King’s Royal: A Magnificent Failure,” The Owen Sound Sun-Times, July 10, 1976.

[3] Croft, 65.

[4] McLauchlan, 33.

[5] Melba M. Croft, Growth of a County Town: Owen Sound, 1900-1920 (Owen Sound: Millman’s Print & Litho Ltd., 1984), 65.

[6] Croft, 180.

[7] “Balmy Beach Pavilion Demolished”, June 14, 1958, from the Owen Sound Historical Society Collection (PF49S18F15I1/A2002.036)

[8] McLauchlan, 31.

[9] Andrew Armitage, “Dominion Day 1899,” Sounding (1987), 5-7.