Sutton Journals

These two journals contain some of Nahneebahweequay’s draft writings on Indigenous rights. The books also served as farm ledgers, as well as containing the writing of William Sutton, brief observations, Bible passages, cures and recipes along with other miscellaneous entries. 1858 petition transcription and correspondence relevant to activism for the right to purchase land is also found here. The transcriptions can be searched by entering Ctrl+f and entering a search term in the box which appears.

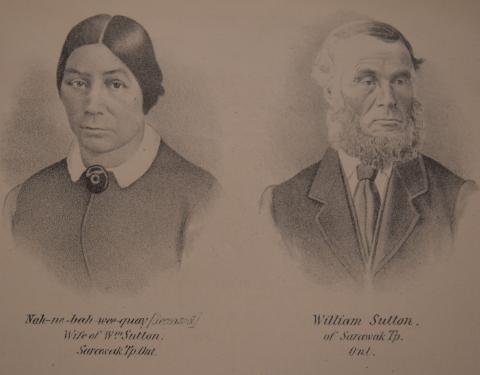

Nahneebahweequay (Catharine Brown Sunegoo Sutton) b. ~1824, Credit River – d. Sarawak Township, 1865

William Sutton b. 1811, Betchford, England – d. Sarawak Township, 1894

Nahneebahweequay was born around 1824 at the Credit Indian Reserve, in present-day Oakville. Raised by her mother and her Methodist preacher uncle Kahkewaquonaby (“Sacred Feathers”, Peter Jones), Nahneebahweequay grew up as a Christian and was educated to read, write and speak English as well as her own language, Anishnaabemowin. She spent her life trying to bridge the cultural conflict between Indigenous peoples and newcomers.

Her personal life embodied the cultural accommodation she hoped would occur. In 1839 she married William Sutton, an Englishman 13 years older than her. He had arrived in Canada in 1830, settling first in eastern Ontario. In late 1838, he and Kahkewaquonaby, Peter Jones, of the Credit Mission met. Soon Kahkewaquonaby introduced him to his niece. When the Credit band were moved off their lands in 1846 to resettle at New Credit, the Sutton family and a few others accepted the Nawash band’s offer of land, relatively far from settlers at the time. In the 1851 census Charles Keeshig recorded that the Suttons were living on a cleared farm in the future Sarawak Township. Passionate Christians, the Suttons were serving as Methodist missionaries and farming instructors at Garden River, near Sault Ste. Marie during Treaty 82 (1857), which surrendered the remaining Nawash lands in Grey County. For the rest of her life, she fought for redress against the terms and the methods of the treaties of the 1850s. Upon her return to the area, she organized her Indigenous colleagues to attend the public auction of their lands to buy them back. Their purchases were subsequently disallowed, on the grounds that Indigenous people could not own private property. Nahneebahweequay in particular faced racism and sexism; she could not buy back her lands because she was Indigenous, but her “Indian” status had been annulled by the 1857 Indian Act, since she was married to a white man and she could not move to Neyaashiinigmiing (Cape Croker) with her community. For the rest of her life, she wrote, travelled, translated and advocated for her people. On September 26, 1865, Nahneebahweequay passed. After her death, William Sutton was able to obtain a deed to the land.

Nahneebahweequay was designated a National Historic Person by Parks Canada in April 2021.

![1961.027.051 William Sutton, [1860 - 1870] 1961.027.051 William Sutton, [1860 - 1870]](/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/1961.027.051_william_sutton_1860_-_1870.jpg?itok=JGJ8YdvM)