Black History in Grey County

Black citizens have been a part of Grey County since the very first non-Indigenous settlers arrived in the northernmost part of the Queen's Bush. Some of these early pioneers were born in Canada, while others had only recently slipped the bonds of slavery in the Upper South. All contributed significantly to the settlement of the last available land in southern Ontario in the mid-nineteenth century.

After a long and arduous journey to freedom, the escaped slaves arrived to discover even greater challenges awaited them. Racism frequently overshadowed every effort the Black settlers made to begin a new life. Insecurity and uncertainty in border cities often propelled people to move further north into Ontario. Indeed, one of Grey County's most prominent early Black citizens, John Hall, had been born in Amherstburg, Ontario, but was captured in a border raid as a young man and sold into slavery in Kentucky.

Several important Black settlements existed in Grey County including Nenagh and Virginia (now Ceylon) in the southern part of the County, Artemesia Township, around Holland Centre in the middle, and Owen Sound in the north. The small village of Priceville in southern Grey County sprang to life very early in the settlement history. Amongst its earliest pioneers were both free Black citizens and fugitive slaves, seeking to establish a community for themselves away from bounty hunters and common prejudice. By the 1840s, few settlers had set up homesteads in the north end of the Queen’s Bush, so the area seemed fresh and open for the freedom-seekers. Some of these early residents included James M. Washington, Christopher J. Simons, Abraham Sheffield, James Handy, Philip Washington, James Jackson, Debbera Sheffield, Ellen Handy, and John Handy. Many of these individuals practiced trades, although a good number of them also farmed the land.

The vibrant Priceville community initially flourished. Additional European immigration of the 1850s changed the district dramatically. Although some individuals struggled to hold on to their lands, the new arrivals often forced the older residents out. Many made their way to Collingwood, Owen Sound and elsewhere. By 1930, little evidence remained in Priceville of the early Black settlement, except for their gravestones. A white farmer decided to remove the gravestones and plant potatoes on the land. The quest to uncover the early history of Priceville and restore the cemetery has taken the better part of the last 70 years.

In central Grey County, south of the small village of Williamsford, the fertile, yet sparsely populated land along Negro Creek and Negro Lake naturally attracted pioneers in the mid-nineteenth century. Freer of some of the prejudices and discrimination in the more developed areas of southern Ontario, by 1851 some 50 Black families made their home in the Negro Creek district. Some of these families may have made their way into the area shortly after the War of 1812, even before local Indigenous people had negotiated and signed an official treaty (1836). The name Negro Creek appeared on a Patents Plan (No. 46) for Holland Township, on December 29, 1851, indicating that the community was well established by that time.

Although few of the original Black pioneer families remain in the area today, some of their descendants can be found in neighbouring communities. The Earll, Douglas, Miller and Bowie families, amongst others, cleared the forests and ploughed the fields around Negro Creek and Negro Lake. Lot 11, Concession 1, South West of the Toronto-Sydenham Road stayed in the Earll family until Solomon sold it to Robert Webster in 1906 and moved to Owen Sound. In addition to farming the land, in later years many of these settlers and their children mined marl (a stone rich in calcium carbonate) out of Williams Lake.

A section of Owen Sound, north of 18th Street East, along 3rd Avenue, received the colourful name of “Mudtown”. The limestone bluffs east of the factories tended to have water run-off and mud slides in the spring, choking the streets in this low-lying area with mud.

Black residents first moved into the neighbourhood in the 1880s. The Polson shipyard employed a large number of workmen and the sudden influx of workers to town necessitated affordable housing. Some landowners built small houses in the vicinity of the shipyard for the families of these workmen and labeled the area “Polsonville”. As other factories, including the National Bolt, Screw and Wire Company and McQuay’s Tannery opened along the east shore of Owen Sound, factory workers who could not afford to keep horses (and later on, cars) tended to live in the area so they could be close to their workplaces. The state of roads and sidewalks, worsened every spring by the run-off from the nearby cliffs, quickly inspired locals to call the area “Mudtown”. In 1920, city residents held a contest to rename Mudtown, so that it would not have such a bleak name. The official new name chosen was “Northcliffe,” in honour of a British statesman. Neither Polsonville nor Northcliffe captured the imagination of residents, and they continued to refer to the neighbourhood as “Mudtown”.

Many neighbourhood families struggled to survive on factory incomes. The Northcliffe Mission opened in the early 1930s to assist people stressed under the crush of the Great Depression. Neighbourhood children, unaware of the economic difficulties, enjoyed the freedom and openness of Mudtown. The cliffs, hills and wooded areas provided ample space for childhood games and adventures. Some of the surnames in a 1932 directory show some Black families lived in the vicinity of Mudtown: Douglas, Booey, Scott, Morton, Earlls. Just above the hill, on what is now 8th Avenue East, north of 16th Street, the street bore the name of the first family to settle in the area. The Douglass family, an African-Canadian family, lent their name to the roadway, and it became known as Douglass Street.

Individual Black families made homes for themselves elsewhere in the County, but these settlements flourished and swelled with a population ready for challenges and hard work.

In the first half of the twentieth century, Owen Sound developed as an industrial and shipping hub on the Great Lakes. Factories lined both sides of the City's harbour, and employed hundreds of local residents. Factories such as the Canadian Malleable Iron Works, Circle Bar, Noma Lites, RCA and Wm. Kennedy & Sons hired Black workers. Often these workers faced hiring discrimination, particularly in difficult economic times.

Seasonal employment was available on the schooners and steamships of the Great Lakes, which stopped frequently in Owen Sound. Often Black men worked as deckhands or cooks. By the early twentieth century Black women sometimes joined their husbands on the boats, also in the kitchens or in housekeeping. Since they were away so much, the people working on the Lakers would put on special events when they were home, such as the famous "Sailors' Suppers," to raise money for the British Methodist Episcopal Church.

Some enterprising individuals made names for themselves in the local community. William Henry Harrison's career as a quarryman in Owen Sound arose during an important era of civic construction in the city. In addition to local work, William Henry Harrison also shipped stone across the country, including the quarrying, plugging and feathering of stone for the locks at Sault Ste. Marie. Amongst other local projects, William Henry Harrison worked on First Baptist Church, St. Mary's Separate School, cement plants, and several local stores.

The Cousby family displayed remarkable ingenuity and resourcefulness in Owen Sound's early business community. Jeremiah's confectionery (sweet shop) enjoyed great popularity, in large part due to the ice cream and Coca-Cola that his main street store offered. Cousby's confectionery was the first to sell the carbonated beverage in the city. In 1907, Jeremiah was voted the most popular merchant in Owen Sound. Jeremiah's son, Jeremiah junior (Jerry), learned from his father's example of hard work and determination and applied himself to his studies. Jerry Cousby practiced law, and co-owned the local newspaper, Owen Sound Sun (1897-1899), before seeking his fortune in the Alaskan frontier in the early twentieth century.

Some community members have succeeded to high levels of musical success, including opera singer Wilson Woodbeck, and musician and actor Tommy Earlls. The Sea Island Merry-Makers knew great popularity on the local scene in the mid-twentieth century. Church life, and an active social community including groups such as the Black (Prince Hall) Masons and the Daughters of the Eastern Star, has ensured that the local Black community could find and draw strength from one another, and participate in the larger community as well.

Grey County's Black heritage stretches back to the early days of settlement. Controversy, challenge and triumph mark the paths of individuals, and Black communities. The legacy of earlier generations lives on at Negro Creek, Priceville, Owen Sound, and elsewhere in Grey, as modern citizens work to ensure the contributions of these important pioneers are not forgotten.

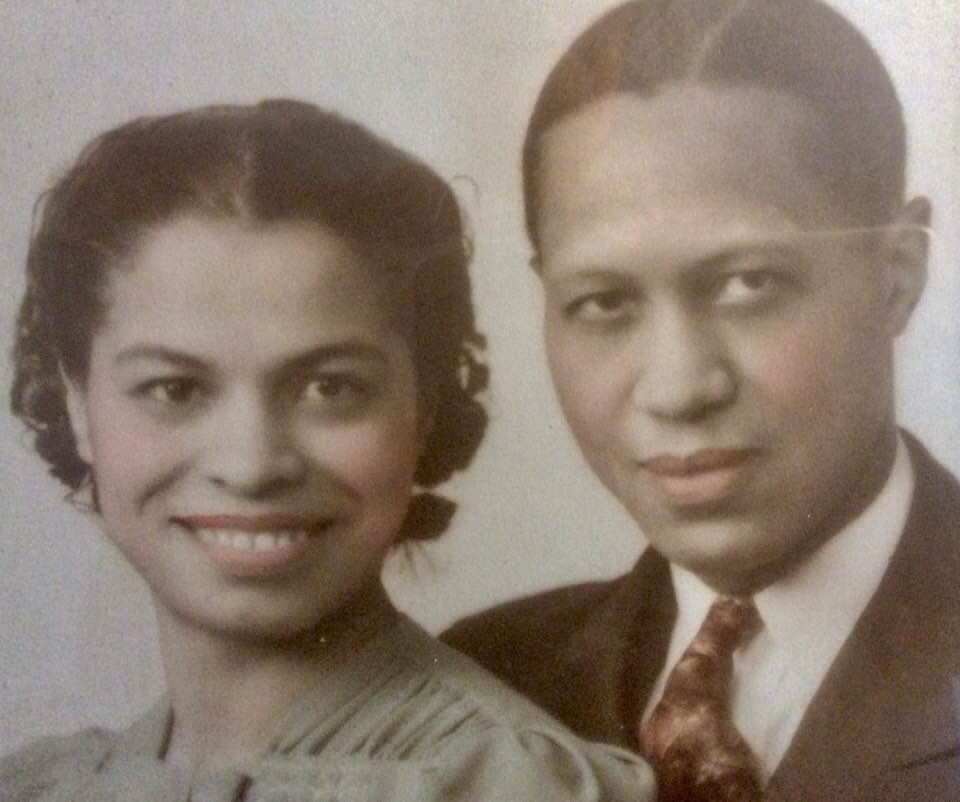

Meet some of the Black citizens of Grey County…